Finding solutions to weird equations

A while back, on social media, I found a link to an interesting post on solving a particular mathematical equation. Now I know this description might not sound very enticing; people solve equations every day! But, some equations carry more meaning than what appears at first glance.

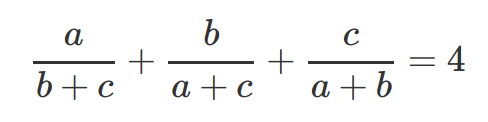

The equation has a pretty symmetric structure and a simple definition:

And we want to find the positive solution or solutions to this equation. How? As will be clear, brute forcing won’t be enough, so we have to study the properties of this equation and come up with ingenious methods.

The post then explains how we are dealing with a 3-degree equation that has at least one rational (but not positive) solution. This means the equation describes an elliptic curve: by mean of complex (and quite boring) transformations, we can express it in the usual elliptic curve form, which is

y^2 = x^3 + ax + b

with a and b rational coefficients of the curve. At this point the post author provides one solution for the equation, the point (-100, 260). By simple math, the corresponding values of the initial unknowns are computed as 4, -1 and 11. So this is not good, because it’s not a positive solution. Now, we can make use of some properties of elliptic curves to find new solutions to test for positivity.

In particular, elliptic curves are closed under addition: adding two points P and Q on the curve yields another point on the curve. Such point is found by drawing a line connecting the two points, looking for a third point where the line intersects the curve, and taking the point that is symmetric to this on the x axis (which will also belong to the curve).

Now, if we add our initial point (-100, 260) to itself, finding 2P, 3P, etc… and every time we test the new point to see if the unknowns are positive. We have to arrive to 9P to finally find the following solution to the equation:

a=154476802108746166441951315019919837485664325669565431700026634898253202035277999, b=36875131794129999827197811565225474825492979968971970996283137471637224634055579, c=4373612677928697257861252602371390152816537558161613618621437993378423467772036

well those are huge numbers, so you can see why employing brute force wouldn’t have helped here.

But why did we pick a point and started adding it to itself? Well it turns out this point is the one and only generator of the curve, so by adding it to itself enough time you are able to find any other non-infinity point on the curve. So if the positive solution existed, we were bound to find it with this method.

The final interesting thing is that the number of digits in the first positive solution we can find with the generation method depends on the coefficient on the right side of the equation (here, 4). The bigger this coefficient, the bigger the number of digits is going to be. How bigger? Can we find a correlation between the two quantities?

Unfortunately, we cannot. This is because there is no algorithm for finding an integer solution to a Diophantine equation, so naturally we cannot make statements about the property of such solution. We cannot even know if one will exist in advance. Thanks to this post, I am now aware of the story behind this, which I might explore in more details in a future post.

Extra notes

I am temporarily without my main laptop, using a Chromebook (long story). So I don’t have access to my usual writing environment and I wrote this post entirely on Github. I have to say that the general flow is quite good: it’s easy to upload a bunch of new files to some location and create a commit, and the Markdown editor is decent with live preview. I still prefer Atom for that though :)

Also, embedding LateX in Markdown, at least for Github Pages, is still a messy affair. Perhaps one day I’ll find the patience to figure out which method actually works and does not require complex HTML code. That day is not today, sorry, you get the equation as a PNG image cut from a screenshot :D